|

As the mother of Milkids, I have oftened wondered how they felt about their experiences. Thankfully, they were willing to share. Their war. Their voices.

0 Comments

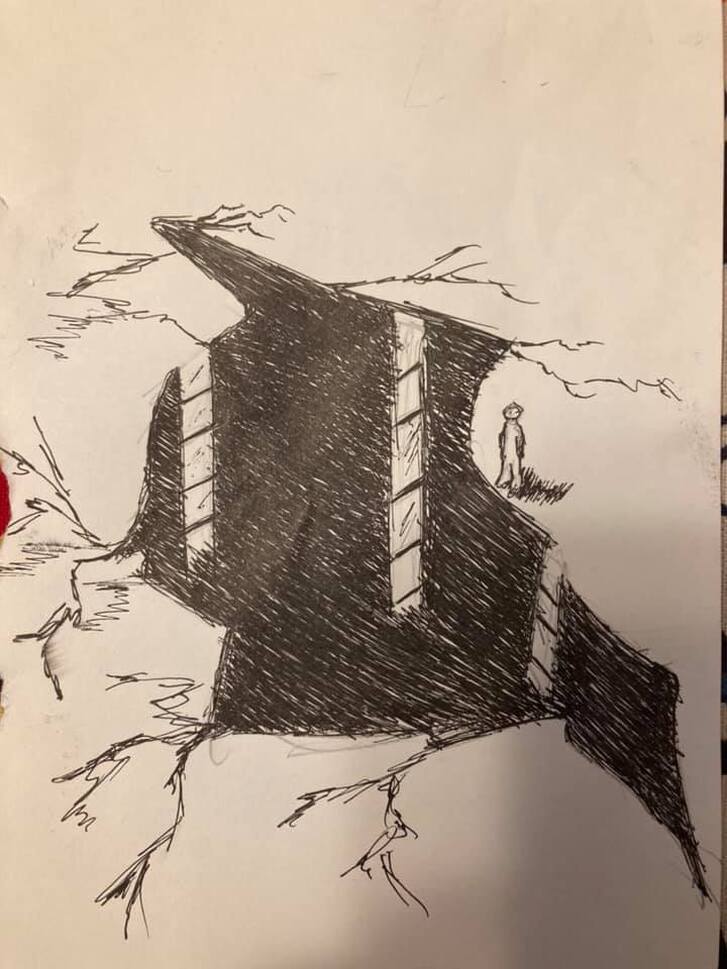

We are a wounded warrior family, and when I tell people I am my husband’s caregiver, I immediately let them know he has all his limbs. Part of this is from my guilt in knowing so many who do not have their limbs, and probably guilt that he came home and so many I know didn’t. The other part is that the wounds he has are all internal, and when people meet him, they immediately question how I could be a caregiver. Or how he is wounded. This feels like a fair question to me given how I feel the conversation must happen in order to build bridges of understanding. For my kids, it has been a different journey. They are now well versed in trauma, seeing me carry him on my back when his back goes out, watching him no longer be able to do the things he loves because his body is broken, and the deep, darkness that a TBI (traumatic brain injury) can bring. It is hard being teenagers who just want normal, and know that will never be the case. It is hard for them to explain why he forgets or needs help with small and big things. It is hard for them to understand. It can be even harder having this conversation with their friends. And yet. They give it all they have every single day. I can’t possibly fathom how they have felt so many times. And while they talk to us openly, we also know they hold so much in, too. A couple of days ago, my daughter drew this. And she wanted all those mil kids out there...those like her...to see it. She speaks. And she inspires with her truth. This piece is called “The TBI Hole.” ~Melissa Afghanistan. Almost everyone in the military has some tie to that place. For me, my dad was deployed to Afghanistan when I was really young. While I can’t remember every detail surrounding multiple deployments, I knew my dad was gone a lot. My mom told me stories often about how I would slam my head into walls and hardwood floors out of anger, or scream at the top of my lungs during his deployments.

While I can’t give many details about that time in my life, it deeply affected me and how I lived. Though I was still a baby when he was in Afghanistan, I knew I was hurting for my dad. Even if I didn’t know why or where he was, I missed him with my entire soul. I remember this feeling during his third deployment, especially when he would miss ballet recitals, soccer games, school events, and day-to-day life. By the time I was 12, he had missed about 80% of my life, and all I wanted was my father to be present and to come home. As I grew, I started learning more about what my dad did, and why he had to leave so often. The looks that adults gave me when I told them my dad was in the Army started making sense. I distinctly remember not exactly knowing the weight that the word “deployment” carried, but I knew that’s what my dad was doing. I’m 17 now. I know so much more about that period in my life. I know more about why he was deployed, and I know how to rationalize and come to terms with how I handled his being gone. And while I had learned the “why” he left, I hadn’t really focused on “how” he left. Or what that meant. August 26th, 2021 the day the suicide bombings in Afghanistan happened and Afghanistan fell, was a day where my whole family had fears and questions as we sat watching the screen. The burning question that I had was, even though I knew more about the big picture, “How was this going to affect my dad?” And once I had time to let that question move out of my mind, I started seeing that it was affecting me too. I kept asking myself “What was the point of him leaving? Had I lost 80% of my childhood for nothing?” Because of the time I had to step away, I realized that deep down I was still a scared little girl, and seeing everything in the news was bringing that out of me. I was scared that these events were going to pull my dad back into the hole he had fought so hard to climb out of. I felt alone. I felt like I was the only one who knew this pain, the only one who was witnessing my dad struggle to come to terms and accept all he had been through, all we had been through. I was so used to living in places with other military kids or families close by, and for the first time in my life, I was watching a military-related event through the eyes of a civilian lens. I became a civilian kid after my father was medically retired, and I didn’t realize how different I felt from my peers until this moment. No longer were there military kids, that I knew of, to talk to at lunch about how out of control everything felt, or just to joke around with. I was watching people flick through the news and mutter “sad,” and move on, which wasn’t how I wanted people to respond. It wasn’t what I needed, but how could they know that? I wasn’t saying anything to anyone, and I was working to make my life look like nothing was wrong. I wanted so badly to be able to feel normal about this, to not feel like I was watching everything my father and so many others had worked for crumble. I spent days thinking about how ‘horrible’ my peers were for saying this, then I realized I was projecting hardcore on them. I was incredibly angry that they weren’t reacting the way I was, and I took that as they didn’t care, which made me the bad guy in this situation. If therapy has taught me anything, it’s that anger is a secondary emotion. I wanted so badly to feel normal, to not feel like I had a personal tie to another country I had never been to, to not feel a deep sinking dread, to not feel like the one out of place. I wanted everyone to sit and stop and cry with me, which wasn’t fair in any way whatsoever. The anger I was projecting onto people was covering the fear and sadness that I could have lost my dad, like so many others who had, and it would have been for nothing. And I was jealous that other people my age didn’t have to deal with those feelings. “How can we just move on from this, from people dying or coming home changed forever, only to have what they were fighting against wind up winning?” I often, and still do, ask myself. I felt my family had ownership over Afghanistan as if my dad were the only one who was protecting it. While I knew that I had a right to my feelings, many of my mom and dad’s friends, as well as my friends’ parents, had been deployed to the same places he had, so I couldn’t have been the only one feeling this. To help try to sort out what I was feeling, I resorted to the news. I had always been relatively caught up with the news and social events, but checking the news became an obsession. My phone became clogged with headline after headline after headline, all detailing the same event. The feeling of loneliness seeped into my sleep schedules. This feeling kept me awake at night, which made me lose much-needed sleep on school and work nights. I started isolating myself from friends, only responding to my best friend and my parents. I was angry all the time. That anger came from feeling like all that my dad had gone through, such as being 100% disabled, his brain and body being forever altered, had been meaningless in the long run. That he could have never come home. And while I felt all of this, I got a message from a friend who saw me. She asked me if my family and I were ok, and took the time out of her day to say “Hey, I see that you’re having a rough time. Is there anything I can do for you?” I remember being shocked and had to ask what made her ask. When she said it was related to Afghanistan, I felt a lot of emotions all at once. I wanted to cry from relief, and laugh from the happiness that I felt seen. And while I felt these emotions, I started thinking about how I hadn’t been a “good” military kid. And then was frustrated that I had decided there was a good or a bad. Why wasn’t there room for feelings to just be okay? But what really began to bother me was that I had been so focused on myself. I hadn’t thought about Gold Star teens the way I should have been, and I apologize for that. I realized, that in being so wrapped up in my feelings, there were people who had never known one or more of their parents, and the Gold Star Teens especially had to be struggling the most. While I did have a father who had come home hurt and forever changed, he had come home. I felt enormously guilty that I was so wrapped up in this when I was still able to see and be around my dad, while others would give nearly anything to even have the feelings I was having. I realized, in a sense, that I had become as naive and absent-minded as I had thought my peers were because I wasn’t seeing the people who had lost lives to this war. I had become what I was so angry with because I wasn’t seeing beyond myself. The ironic part is it took a civilian to show me how to be the kind of military kid I want to be. I decided to take the lessons she had given me, and use them to help others. I started creating a lot of art, using all the emotions I had been feeling before she reached out. I had always been drawn to language and the written word, so I decided to do what she did, and I am writing these blogs to reach out. I never would have been inspired to speak had it not been for my civilian friend, who taught me to be the kind of military kid I want to be, and how to start this dialogue. So, I’m here. I’m here to talk, no matter your background. I’m here for your feelings, your questions, and your answers. I’m here to speak. Mia Seligman is the 17-year-old daughter of a medically retired veteran. She moved to Asheville when she was 12, which was the sixth place she had lived. Mia enjoys listening to records, playing electric guitar, and thrifting with friends. I think it’s pretty safe to say that 2020 sucked. We experienced people dying in the streets, a pandemic that seems to be lasting forever, and the dreaded online school.

For many military kids, the amount of chaos felt familiar. Having to make peace with the fact that there was still a lot of information that we didn’t know, people we knew were dying or having lifelong health issues, losing contact with loved ones-the works. While it was difficult, it was shocking to me how similar it all was to a deployment. Parts of me fell into a sort of calmed state due to the repetition of this part of my life. A lot of the same feelings came up for me that I felt when my dad was deployed. I was angry that I didn’t know what was happening, scared because things felt like they’d never get back to normal, and frustrated that parts of my formative years were being ripped away. I realized that I was starting to spiral into a fit of anger and fear I hadn’t felt in years. I was yelling at everyone in my family, isolating myself from everyone I knew, skipping things I knew would help my mental health, and taking my anger and fear out in unhealthy ways. I had resorted to a lot of my old coping mechanisms, most of which was a subconscious action. When I was in third and fourth grade, I struggled with knowing there was nothing I could do to keep my dad safe, that it all felt out of control. I used to wake up every morning and play animal jam on the family computer, or I’d read fantasy book after fantasy book, over and over again. While these were small actions, they were in my control. About halfway through the pandemic, I logged back into animal jam, for no reason I could pinpoint in the moment. I dug out my books from fourth grade and lost myself in the mediocre plots. And for a while, I was in control again. If playing old video games and reading kids' books during a worldwide pandemic and political unrest taught me anything, it’s that the military and what you learn during that time never leaves you. I had hated almost everything about being an army kid. I always felt like I was the only one in my class who had never had the chance to have a best friend or to feel like I had secure roots. I blamed my dad for a long time for leaving us, even though I had known it was out of his control. I knew blaming him was unfair to him and my family, but it was easy. And while I felt all these rising feelings, I could draw the parallels much more easily. I knew that escaping into a world where the worst thing to worry about was whether or not your spiked collar was rare, or if Percy Jackson would make it out of the labyrinth alive, was a way to focus on what didn’t feel crazy and terrifying. I knew from years in the military that escapism can be a coping mechanism, and that’s ok. While the military portion of my life hurt, it taught me how to stay calm and manage day-to-day during a crisis. How to remain grounded when everything and everyone around you seems to be floating away. And if that means playing animal jam and rereading Percy Jackson books, then that’s how I needed to support myself. 2020 was a hard year for so many different reasons. I had seen and experienced this before, though. In the beginning, I couldn’t put my finger on why I was so mad, but then it clicked. I was scared, and my subconscious was telling me that my dad was deployed again, which obviously didn’t make sense. He was still here, but that didn’t change the fear. However, I knew that I had fought for what I had needed in order to heal and become healthier. I knew that I had a support system that cared for me and I could rely on, and I knew that holding all of my pain and anger, and fear it wasn’t going to be helpful for me, or anyone else. Sharing your experiences, and letting others in, is the only way to move forward. Even if you feel like how you were coping wasn’t “normal”, who’s to say? We’re living through something that we were never prepared for. I can promise you that you aren’t alone, though. I felt a little crazy as a 17-year-old playing a game meant for kids under 10. But, if the military had taught me anything, it’s that what is helpful and makes me feel in control is what is normal. And I believe military kids are creating that normal. Mia Seligman is a 17-year-old daughter of a medically retired veteran. She moved to Asheville when she was 12, which was the sixth place she had lived. Mia enjoys listening to records, playing electric guitar, and thrifting with friends. Out of the mouths of babes

There truly is no understand of what it means to be a military child unless you've actually been one. All in all I believe that being a military child has changed my outlook on life. But I don’t really know where to start. Or how to explain it. My dad was deployed when I was younger so I was lucky in that. If It had happened when I was older I think I would have grasped that he had the chance of not surviving. I would have had a lot more emotional stress and miss him a lot more since I wouldn't see him. He helps me believe in everything I do and supports me in every way. I just finished reading my mom’s book and it was about his second deployment. And it was a sensational book. It showed me how lucky I am to have him. When he was gone for work I was a bit older and I could talk and walk. My mom worked hard during those times to help other families. My mother had meetings with her wonderful team. My sister and I would talk to each other, play legos, have nerf wars, and watch tv. One time my mom was on a meeting and we made a sign that said “can we watch tv?”. Not my finest moment, interrupting my mom’s work. But when he was at work and not deployed I didn’t have too much fear and anxiety. I knew everything would be okay. Being a military family we moved around quite a bit. I have been in many houses and have several memories. One of the things that was horrible was having to leave behind many friends. Every time that I had a good relationship we moved only to start over. In Alabama I met this one friend. He was probably the nicest boy around. He was funny and amazing to be around. Another boy I met, I don’t even remember his last name. At my 10th birthday party he tried Takis and had the sink sprayer sprayed in his mouth. I miss his weirdness. While in Alabama I met a friend who played baseball. I played baseball with him and he was amazing to watch. We had him over a whole bunch and I miss him. When people talk about military kids, especially during this month, most people think of those things: deployments, or schools, or having to move a lot. But being a military kid does not just mean that you are the child of a military warrior. It means you endure the strength and pain of family being split in two. My mom stayed with us during this time. She stayed strong in protecting two children. She stayed home and worked and took care of us at the same time. When we were sick we got sick. I threw up in the bathroom. Not just in the bathroom, I threw up on the walls and floor and on the toilet. It was horrible for her. Not for me. I didn’t have to clean it. I am so thankful that I have my wonderful parents standing by me. I rarely like to leave their side. I am blessed with these two amazing people in my life. So whenever you talk to your parents and friends thank them or acknowledge them for all their hard work and effort that they put into your life. Because being a military kid is about all the hard times. The sick times. The moving. The sadness. The crying. And, hopefully, it is also about finally having a chance to be a family. Identity is something every child struggles with, as simply a normal part of growing into an adult.

Who am I, what shall I become, what is my place in the world? There's the added weight of the expectations of the adults in the child's life, trying to direct and steer them into the directions the adults feel is best. Then there's the military child. All of the struggles, the weight, with the added weight and stress of the label of military dependent. Who are they, what will they become, and how will they get there? Blankness is a darkness that falls on ourselves. Darkness is light. But seen a different way. Light is the fire that burns us. Determination. We keep these in our hearts. We think. But in our own way. And they say we are all special. In our own way. We love. In our own way. We are special. We just need a chance to realize it. PTSD is a difficult disorder to live with. It's difficult to understand, not just for those living with it, but for those interacting with those who suffer.

Trying to explain what's going on to your children is a whole new level of difficult. And there is guilt, that it's just one more thing we've put on their shoulders. But, we have access, through mental health professionals, counselors, and support networks, to tools we can teach our children to use; tools they can use to not only understand what is currently going on, but their emotions and feelings as well. "I guess I can't have anything of mine in this house!" My Dad yelled at my sister after she threw his magazine away. It was an old magazine and I didn't know why he was mad. He yelled at her for what felt like forever, and then yelled at me for standing there. I went to my room and cried. When my Dad yells like that I don't feel good. My stomach hurts and I want to bury my head in my pillow. Sometimes he yells really loud and it scares me. My little sisters start to cry and I cuddle with them on the bed. Pretty soon I hear my Mom talking to my Dad, and he stops yelling. He comes into my room and he is crying too. He says sorry and gives me a hug. Sometimes I don't want him to hug me. Sometimes I want to yell at him and hurt his feelings too. But I don't. I'm too scared he will yell back again instead of being sad. I wish I wasn't scared. My Dad says he has something called PTSD. I don't really understand what it means, but he tells me that it means he is not the same anymore. Something in his brain isn't working right and he gets angry faster than he did before he went to war. My Dad sings me a song and rubs my back while I cry. The anger builds up again. How can he be so mad one minute and be so nice the next? It confuses me. I want to be angry at him and I want to hurt him like he hurts me, so I tell him that Mom will divorce him if he doesn't stop having tantrums. I think I must have hurt him because he stops rubbing my back and leaves the room. I heard him whisper "I'm sorry" again and then I hear the front door close. He has left. Now I am the one who is sad. I didn't want him to leave. I just want him to not be so angry. I write in my journal and put it on my Mom's bed. I can hear her crying when she reads it and then she puts it back on my bed. The only thing she has written inside is "I love you. No matter what." I start crying again and hug her hard, telling her I am sorry for saying that to Daddy. She says that we will all work it out. Maybe she called him, or maybe he was done being sad, but he came home. Mom and Dad talk in their room for a long time. I can hear whispers but I don't know what they are saying. Later they both come out and I can see Mom has been crying. I hope she isn't really going to divorce him. I didn't want that. I just wanted him to know he hurt me. Mom gives me a hug and goes to the kitchen. She cooks or cleans when she is upset. Dad asks if its ok if he sits with me. I nod and he sits down. He doesn't say anything. He just sits there. I think he doesn't know what to say to me, but thats ok because I don't know what to say to him either. We sit there for a long time. We don't say anything, we just sit there. Then he stands up, and says " I love you so much." and walks back to his room. Mom tells me that Dad doesn't have someone he can write to when he has bad feelings. I told her he should get a journal like mine and then he could write to her, but Mom says Dad needs someone else to talk to and he is going to call about going to a counselor. I went to a counselor before when I was sad and she helped me, so I think this is a good idea. I wish I could help my Dad, because I want him to be the fun Dad he used to be, but Mom says sometimes it takes more than love to help someone. I hope he can talk to the counselor and be the fun Dad again. What is it that makes us who we are?

For a military child, that is a vastly different answer than many other children will ever be able to know. Yes, it is a difficult life. There is a lot of loss. But, there are so many small, brilliant joys, that bring beauty out of the seeming chaos of that life. Here is some of all of it. I am from packed up rooms I am from different yards with crabby old neighbors and mean old dogs barking everywhere, as my brother and I played in our tiny yard. The trampoline was our favorite. I am from a different neighborhood every 2 years, with different ‘‘Neighborly’’ welcomes, including dry cookies and phone numbers. I am from Eleanor and Darryl slipping snickers bars through the fence, acting as My adoptive Grandparents, and Melissa holding me close as I wept for My daddy. I am from “we’ll get through this. Daddy will come home. He won’t stay in Iraq, he will come home.” I am from blueberry muffins as a deployment coping regular, and macaroni and cheese and hot dogs. I am from Latkes and Dumplings, and tacos and eggs with cheesy biscuits. I am from the one journal that has never touched the inside of a packed up box, but was never finished, for they carry into another journal, instead of the last page. I am from letters from friends I will never see again, who I feel guilty thinking about. I am from learning how to say goodbye so I can say hello again. I am from a ragged old doll teaching me how to love I am from several sketch books, that are better than growth charts I am from thousands of songs I am from one ragged old dog, who hugged me harder than I ever hugged him, who is losing his stuffing I am from one Simon and Garfunkel song that daddy rocked me to sleep with I am from a legacy of houses I will never forget, and make sure the next generation knows as well There are deep, unrelenting emotions hidden in the words of children telling you of their feelings facing stress and separation.

The words might not seem deep, or as cunning as the words of an adult, but children are, as they experience things, learning the words the adult they will become will use to more fully describe not only those emotions but how they have learned to handle and live with them. As they speak, we are privileged to watch them grow and understand the world and who they are in it. Sometimes that is beyond painful, emotionally. Especially when they are our own. And so, when listening to a child talk of their emotions, their fears, their worries, it is raw in the way many of us have learned to forget, to cover with distractions. Sometimes, the simple words are the best. Witness with us. Out on the boat Without me For so long Oh, so very long Dad is gone. Counting down weeks til he’s home We miss him so much. Angry. Sad. Confused. Worried. Scared. Annoyed. Trying not to think about it. Trying to be ok. |

Details

AuthorAll the blogs found here are from military kids. Archives

July 2022

Categories |

OPERATIONAL AND PERSONAL SECURITY

We look forward to open, candid discussion but we want to ensure everyone understands and adheres to Operational Security (OPSEC) and Personal Security (PERSEC) standards. Please read the information we have provided on OPSEC and PERSEC. Thanks. ~ Melissa

We look forward to open, candid discussion but we want to ensure everyone understands and adheres to Operational Security (OPSEC) and Personal Security (PERSEC) standards. Please read the information we have provided on OPSEC and PERSEC. Thanks. ~ Melissa

|

© 2016 Her War, Her Voice. All Rights Reserved

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed